Better to be in jail than on the streets

This is the story of the unhoused in Montreal during a frigid cold. This is the story of Resilience Montreal, and David Chapman’s daily grind. This is the story of a society in decline.

As always, in my commitment to trying to innovate, this video can either be watched in full, or read with portions of video stitched in. The full bibliography can be found here.

I have made this article with two choices— you can watch the documentary in full, or you can read my narration and watch sections below.

It was minus 28 degrees Celsius outside the morning of December 6th. An early frigid cold that none of us could have predicted showed up on our doorsteps, one that none of us saw coming. It had been this cold for a few days straight, and would continue until early January. It got worse during the winter holidays.

I had a ton of work to do. Instead of doing any of it, I called David Chapman, who runs Resilience Montreal.

Resilience is a homeless resource in the city. It feeds 1200 meals a day, has space for beds, a small heating tent, social workers, and gives people clothes and support year round. Running the centre costs $2 million a year. I called David and asked him to do an interview. When I got there, the first thing he showed me was the most recent memorial they held for those who have died in the past 18 months.

32 Dead

32 dead in the past 18 months, he said. Bodies found on the street, not a news announcement to inform us that this happened. I text David every once in a while to find out about those who’ve died, about the conditions on the streets. These people, disproportionately indigenous, are swept under the rug. Their families are unknown, and the country has forgotten about them.

In November, Soraya Martinez Ferrada had been elected as the mayor of Montreal with a majority at the Hotel de ville. Her party, Ensemble Montreal, promised to help the homeless. The mayor said “each tent is a reminder that “we have failed as a society.” (CTV)

Strong words from someone who used to be part of the federal Liberal government, the party who has built our society from the ground up.

Within a month, and the rapid descent of the temperature at an earlier date than usual, the new mayor opened up 500 warming shelter spots for the homeless, not places for them to stay, but indoor spaces where they could catch their breath for a minute and sit on a chair or mat. She was quick to admit that it was not enough to solve the problem.

The mayor has approached this challenge with incredible ambition. She promised to end homeless encampments within four years— by the time she’s up for reelection. The way she’s phrased it worries me, since many politicians will get rid of homeless encampments, but not solve homelessness. Still, the mayor seems determined to help, and for my part, I hope she succeeds in truly helping those in need.

Still, I’m doubtful.

Although I had come to make a three minute video about homelessness in Montreal, and the challenges of running a homeless resource, David had other plans. He told me we were gonna visit with some of the people at Resilience, and then we were gonna pack up, and visit the homeless encampments around town. We did exactly that, jumped into his minivan, and hit the trail.

On a mission

One of the worst parts for those experiencing homelessness in Canada is, as you well know, the temperature during the winter. There is rarely a reprieve to such brutal weather, which can last four to six months.

People around the city struggle with cohabitation, living beside their homeless neighbours. Thus they want encampments dismantled. Cities will pose the “end of encampments” as an effort to help the unhoused, but the true motivations are up to debate.

As much as we have to find deep empathy for the unhoused, there are good concerns to consider while we’re at it. Sometimes the unhoused can bring with them some problematic habits. What do we do when the unhoused set up a bike chop shop? What do we do when there is violence, or unrest? There are some fair criticisms, but are these really criticisms of the unhoused? Or are they criticisms of our lack of resources, resources that the government fails to provide?

So the two of us arrived at our first encampment. It was horrible outside. These individuals are doing their best to survive in these dangerous situations, with no place to go to seek help, and no resources available.

David had taken me on a mission. Our goal was to provide these people with different ways to keep warm. So we showed up with our supplies, an open hand, and were here to provide what we could.

Rather be in prison

After meeting with Derek, chatting for a while, checking out his setup, and making sure he and his roommates were okay, David explained how the city could set up better systems for the unhoused while simultaneously saving money.

But they refuse to do it because it lends credibility to the encampments– it’s an acknowledgement that they aren’t doing enough to help these people. It’s an acknowledgement that these people have a right to stay there, and that they deserve more dignity. If the government provides heating, sanitation, and better supplies, they could be pushed further. If they set up a generator, and provide electric lines and a toilet, they would have to acknowledge that they’re failing in some way, and that these people have a right to live here. They can’t do that, because that would change their approach.

You see, although the charter gives these people the right to build encampments and live in these encampments, the reason for that is because they don’t have another option. So, David explained how the city will temporarily provide another option, thus technically fulfilling their charter obligations, and then tear down encampments in response. If there’s another option, even if it’s not a very good alternative, the government has given themselves the right to tear down the eyesore that is an encampment.

Instead, people would rather go to prison than stay on the street. At least in prison, you’re fed and warm.

Homelessness across Canada

Stats Canada says “Encampments, which are outdoor locations with a group of tents, makeshift shelters or other long-term outdoor settlement, where two or more individuals are staying.” An encampment can be large or small. In 2024 and 2025, former mayor Valerie Plante’s administration dismantled many homeless encampments, against every advice. Finally, an injunction was granted against the province, stopping her from tearing down the encampment on Notre Dame.

Although this one story takes place in Montreal, national statistics paint the picture of a country in decline.

Indigenous people are overrepresented in the unhoused population, but because of global unrest and violence across the planet, asylum seekers and refugees have now become a major group who are on the street, homeless.

Just a couple years ago this wasn’t the case.

The number one cause of homelessness is not disability, drug addiction, or anything else of the like, the number one cause of homelessness is housing unaffordability. Thus, those who are arriving in the country, immigrants, temporary workers, refugees, asylum seekers, they often wind up unhoused because of the impossible price of rent. Nonetheless, despite the number of immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in the system, 85% of the unhoused population are Canadian citizens.

It might be high time to declare this a humanitarian emergency in the country, because as it stands, people are dying on the streets in droves, and the speed at which homelessness rates are rising should alarm all of us.

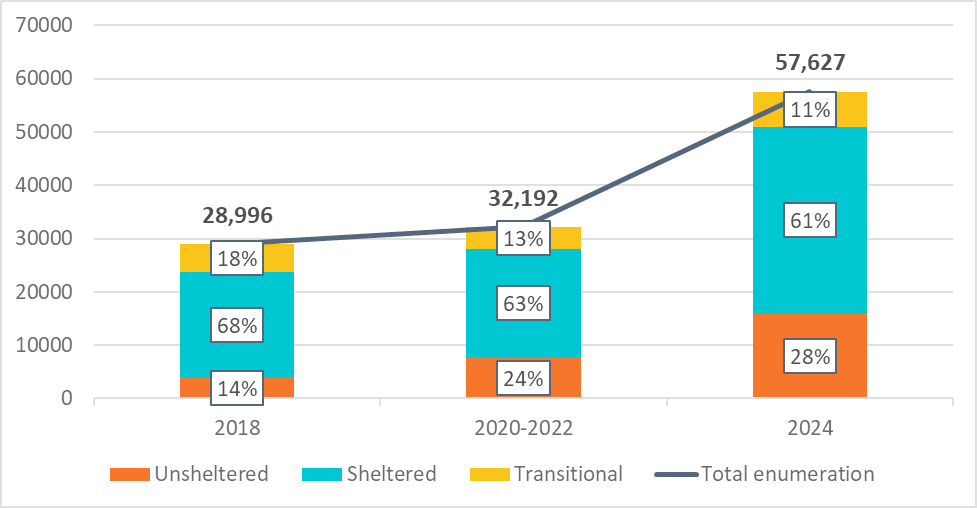

The homeless population has risen by 79% from 2022-2024. At least 458 people experiencing homelessness died in British Columbia in 2023. This is an increase of 23% in the province. In Edmonton, unhoused people grew by 47%, totalling 4,011 people up from 2,728 people in January. In 2024, nearly 60,000 people across Canada are experiencing homelessness every single night. Over six years, from 2018 to 2024, that number doubled. This is based on a study across 74 cities.

Graph taken directly from stats Canada. This is a screenshot. In fact, all of the information is available in the bibliography, and all of the stats available in this section were taken from work done by other people!

The shelters in the city are unable to absorb this. Although there has been a cash flow into homeless resources, it isn’t enough. There are only half as many beds as there are people on the streets. A disproportionate number of people using these shelters are indigenous. 32.5 per cent of all shelter users are indigenous, despite only being 5 per cent of our national population.

A burning ball of paper

We went around the second encampment, over in NDG by the hospital. We talked to some people, one guy told us he hadn’t slept in five days– which could have very well been true, though I was doubtful. Nonetheless, he paced back and forth with a cigarette in his mouth, as though he was trying to get his steps in for the day. We approached dozens more tents. One man invited us into his tent. Inside, he had made a pile of toilet paper, cardboard, and whatever else he could find that was flammable. He lit it on fire, and left it on his table. A ball of flames was there, open, chaotic, filling the closed, canvas construct with smoke and ash. He told me he was cold, and desperation painted his face. Dave and I went off to go find some stuff that would help him stay warm. We rode over to Canadian Tire to see if we could grab something easy, safe, and accessible.

This would cost some money. Something that I didn’t understand was how Resilience managed to survive. $2 million a year to run a homeless resource is an unbelievable number. It’s not abnormal, however.

David explained the impossibility of fundraising. It took tons of coercion, and a lot of lobbying. The resource is on the border of Westmount and Montreal— and Westmount is not inclined to help them. Montreal, on the other hand, is a more reliable partner.

Nonetheless, they fell short of funding it outright. So David spends tireless energy raising money, applying for grants, putting out feelers everywhere. His team has his back, and as much as they struggle to make it every year, they manage to make ends meet. And soon enough, they’ll move into a brand new space that has been specially designed for them.

You see, homelessness costs cities huge sums of money. The country spends $7.05 billion a year on the problem. Housing these same people would cost the country much less, except it would interrupt the culture and idea of the “deserving poor.” The idea that some poor deserve help, and that’s why our programs are targeted. Universal programs, accessible by all, are far too giving. Some people, people who don’t need these programs, they shouldn’t have access to it. If you quit your job, you don’t deserve EI. Only if you were let go through no fault of your own. Dental care, but only if you make less than a certain amount.

If health care were made in 2026, it would have conditions attached.

An oasis in sight

When we arrived back at the encampment, the city was there with a garbage truck, and was pulling apart different places in the encampment. I walked up to them and spoke to a man with a beautiful regional Quebec accent. He was depressed. I asked them what they were doing, and he told me that he hates doing this, and that they only come to tear stuff down at the behest of the city. He also told me they targeted the spots that were clearly abandoned, or which were clearly garbage. To their credit, they didn’t take down any tents, and removed a lot of waste. This time.

Of course, for the cost of sending these men and trucks every day or two, they could have likely paid for the disposal facilities and sanitation that would make this place much safer, with less risk of people burning their tents down out of desperation to heat it.

The final stop we made was for David to show me the building that the resource would be moving to soon. Inside, the construction was almost done. Inside, the multi floor building was exceptionally well thought out to make cohabitation as easy as possible, and everything is done in partnership with the city. Social workers, non emergency staff, meals and sleeping areas, a garbage disposal in the basement, and outdoor smoking area that doesn’t bother the neighbours.. It was the most well thought out resource I’d ever seen in my life. Designed around many indigenous practices of welcoming and homesteading that emphasize Resilience’s commitment to the indigenous community. The facility is likely to change the city. Who knows, with enough press, maybe it could change the country.

Failed society

Soraya Martinez Ferrada, the mayor of Montreal, spoke truly when she said that how the homeless are treated reflects that we have failed as a society. How she will continue responding remains to be seen. But she has taken good first steps with harm reduction. Her ambitions are high, and maybe impossible considering she’s only the mayor of a city without enough resources. In fact, resource allocation is a problem for every part of the country. Social systems are being crushed and defunded.

Not only that, but addiction and a lack of safe supply is killing people. The high prevalence of addiction within the homeless population is a challenge that has yet to be overcome. 61% of people interviewed by Stats Can are users. Their supply is tainted, putting every addict at risk of a sudden, horrible death.

The introduction of fentanyl, carfentanil, and benzodiazepines into the street supply has killed 53,308 people, from teenagers to adults across Canada. Benzodiazepine contamination is particularly dangerous as it renders naloxone (the standard opioid reversal agent) ineffective, complicating overdose response in shelters and encampments.

The government needs to provide a safe supply. There will always be poor people in a capitalist society. There will always be people who get drugs and have addictions. The most important thing is to provide a way out, and there is no way out of addiction if you’re dead.

Toronto’s facing the worst of homelessness in Canada. The 2024 Street Needs Assessment estimated 15,400 homeless individuals, double the 2021 figure. The city has attempted to expand shelter capacity by 60% since 2021, creating new beds faster than any other Canadian city, yet the system remains at capacity every night.

Vancouver’s 2024 count showed a 9% regional increase to 5,232 individuals. Notably, the crisis is suburbanizing: Delta saw a 115% increase and White Rock a 53% increase. The region is battling the dual crises of unsheltered living (up 30%) and drug toxicity. The response has been uncoordinated with the municipalities refusing to share resources. It has gotten much more decentralized and violent after Vancouver broke up the tent city on Hastings, fueling the movement of the unhoused into the suburban areas.

Edmonton has adopted a more aggressive enforcement posture. In 2024, the city dismantled nearly 3,819 encampments, double the number from the previous year.

Halifax was one of the few Canadian cities to officially experiment with “designated encampments” as a harm reduction measure. However, in late 2025, Halifax Council voted unanimously to close all remaining designated encampments within two years.

And now, because people are being pushed away from centralized locations, they are going to small cities. Places where people never saw the unhoused have suddenly become hotbeds of it, with the challenges mounting every day.

We need more shelters. But a court case in Waterloo defined certain needs of shelters as well. A shelter is not constitutional if:

It separates couples.

It cannot accommodate pets.

It imposes sobriety requirements (barrier to those with addiction).

It restricts personal belongings significantly.

This ruling essentially invalidates “enforcement-only” bylaws in jurisdictions with shelter deficits, forcing municipalities to tolerate encampments until they can offer low-barrier housing options. But as David explained, many cities are inclined to create housing, tear down encampments, and then let the program end. Therefore we must address the true root problem.

The biggest failing is clearly that housing is so brutally expensive. And until we correct the housing crisis, we will not be able to end homelessness in Canada. Until life is affordable, and people have mental health services, this will never end.

Until the day we solve the housing crisis, people like David Chapman, and Resilience Montreal are going to fight for this, and other cities.