Ethics Commissioner’s office fails to produce nearly half of MP disclosures after 9 months, no end in sight.

Duff Conacher believes that the Ethics Commissioner does not care about the public’s right to see politicians’ conflicts of interest.

(I did not do a video for this piece, simply because I ran out of time. I’m super sorry! I’ll probably include all of this with my next video, and have some sort of double video.)

The Public Registry for ethics disclosures is missing 150 disclosures almost nine months after the April election.

Of the MPs whose disclosures have been posted, there has been little change in the number of MPs who are landlords. Still, with the information of almost half our MPs missing, it’s impossible to say what the final numbers will look like.

As explained to me by the ethic’s commissioner’s office, the process of releasing MP conflict of interest disclosures allows for an unlimited gap of time with no oversight, as well as no powers of enforcement if a Member does not fulfill their disclosure obligations.

In the spirit of transparency (unlike the Parliament), I have made my recent correspondence with the commissioner’s office available here, the purpose of which is to allow people to see the full context of the quotes if they want to— it won’t change the story, and I feel I have quoted them in context. I have removed names and phone numbers from the emails. It also provides a resource to fully comprehend the conflict of interest disclosures without the usual opaque wall of legal language.

In the federal Parliament, ethics disclosures are required to be submitted by the MP within sixty days of their name being printed in the Canada Gazette after being elected. After they submit their initial compliance, the office looks over it and creates a summary of their disclosure.

“The initial compliance process includes two separate 60-day periods, but the second period does not begin immediately after the first one ends,” a spokesperson for the Office of the Ethics Commissioner said. “There is an unspecified amount of time between the first and second 60-day periods.”

The MP then looks through their information and their advisor will tell them how to best comply with Canadian law. The advisor prepares a summary, and sends it to the MP. The MP might put their assets in a trust, or they could sell their assets to comply with the conflict of interest laws. The latter is less common.

Most MPs who are not in cabinet, or who are not in positions of authority simply disclose their assets, which continue to accrue value while they are paid handsomely for their work, and making invaluable connections in the business and financial world.

Despite it taking 9 months, the spokesperson noted “that the time it is taking for all MPs to complete the initial compliance process following a general election is not outside of the norm.” In many provinces across Canada, this is far longer than the norm– specifically Ontario and Alberta, who have the most robust systems to prevent conflicts of interest and disclose public servants’ assets.

Commissioner Konrad von Finckenstein (pictured on the left above) offered us no comment to our questions on ethics and democracy in Canada. To the questions concerning Canadian democracy & transparency, as well as global democratic backsliding, the spokesperson said that “It is not the role of the Commissioner’s Office to offer comment on such matters.”

“The current federal Ethics Commissioner is a lapdog, who has shown again and again that he doesn’t care about the public’s right to know the financial interests of Cabinet ministers and MPs, and that he is fine with facilitating and hiding federal politicians’ conflicts of interest from the public,” Duff Conacher, co-founder of Democracy Watch said.

Aedan and I have been tracking the people who have been elected across the country, and whether they are landlords or not. Every single province is already available on the website, which is being updated and maintained by Aedan constantly. This database will continue to be updated for every province as elections happen, and as information comes out.

There should never be a years-long delay on the site, and we will actively update it as MPs come and go, or as by-elections are held. Any informational errors will be corrected as soon as they are brought to our attention.

Searchable Database

There is no consequence to missing the two 60 day time limits. We reached out to the commissioner’s office, and asked them if they were imposing penalties on the MPs who missed the date.

Here are the names of every single MP whose summaries are not on the public registry. I have made the database searchable so you can look up your MP’s name.

Aedan Burnett, my colleague, and data analyst, explained what is going on with this info.

Simple Solutions: Aedan’s Expertise

When data is of poor quality and difficult to access, it tends to be ignored and forgotten.

The problems with Canada’s ethics and transparency data in its current state are numerous. It is accessible only through ancient looking web pages that are not easy to locate. The presentation is poor. The timelines for releasing the data are lengthy, and somewhat arbitrary. The rollout of the data in the public registry is arcane and not consistently adhered to.

There is no notification of any kind when information is released– it simply appears. It is buried in the depths of a byzantine web portal, where it is removed without fanfare when an election is called, and no archives are accessible.

Equally frustrating is that many of these problems have simple solutions.

The government could use RSS feeds, or more simply an email list to notify people when the information is made available. They could create APIs to access this information in bulk, or release it in a spreadsheet friendly format like they already do for expense data.

For timelines and delays they could indicate fixed release dates, or create a dashboard that visualizes the current status of documents for each member of parliament.

They could add visible timestamps to indicate when information was released to reduce the burden for archiving. More broadly they could integrate this information with existing, effective government pages such as Ourcommons to make it more accessible to the average Canadian.

Currently it requires significant understanding and technical ability to find, gather, process and archive this information. The fact that a motivated individual is doing this for free on their behalf is not sustainable or acceptable in a functioning democracy.

No enforcement

“The (conflict of interest) Code does not provide for any penalties… The Commissioner may only recommend appropriate sanctions when he finds in an inquiry report that a Member of the House of Commons has contravened the Code. It is up to the House of Commons to impose any sanctions,” the spokesperson said.

In English, what this means is that the commissioner can recommend that the house enforce the code of ethics. The only people who can hold the house of commons accountable therefore, are the people in the house of commons.

Ethics in Canada are a closed loop. There is no interest in the house of commons to impose fines, or consequences– and the recommendation of the ethics commissioner to do so is fairly rare.

Duff Conacher’s company, Democracy Watch, had a date in front of the Supreme Court last week to challenge decision making around the We-Charity scandal from the early pandemic. In brief, the scandal had to do with Trudeau family involvement with the charity, and then the Trudeau government tried to hire out to the charity for work for a contract worth $900 million.

The Ethics commissioner, Mario Dion, said that there was an “apparent conflict of interest” but that it did not break the law.

Conacher and Democracy watch were unsatisfied with the outcome of the report, filing a lawsuit in 2021 to challenge the commissioner’s findings. However, in the court of appeals, the judge ruled that there was no mechanism to overrule a commissioner’s findings– this is due to a partial privative clause. “This is a very common type of clause that parliament puts into laws that govern administrative tribunals and agencies and boards and commissions that make legal decisions,” Conacher said. More simply put– the government can partially shield itself from having court challenges.

Conacher was surprised to find out that the supreme court had never ruled on whether this was illegal under the constitution. They had ruled that the government can’t completely shield themselves, but had never ruled on partial shieldings from court challenges.

Unless the supreme court decides that the government isn’t allowed to use partial privative clauses, the only way to overturn decisions like the We-Charity dismissal is to have the house of commons overturn the decision through committee.

Committees are composed based on party makeup in the house of commons, and make decisions based on a democratic vote. If a party has a majority in the house of commons, they have a majority on committee. If they have 46% of the seats, they get that many members in committee. Only parties with official party status are obligated to get seats on committees, so the Green party and NDP in the 2025 Federal makeup are not guaranteed a seat on committees. Committees are where large portions of Canadian laws are made.

“It’s a kangaroo court, if you’ve heard that term before. By definition, because politicians make decisions based on partisan political bias, not based on the facts of the law. And politicians, as a result, should never be judging other politicians. And that’s why the Ethics Commissioner position was created,” Conacher said. The Ethics commissioner is supposed to enforce the law around conflicts of interests, but can be compromised because of partisan interests making decisions around appointments.

The commissioner is chosen by whoever is the prime minister at the time for an appointment of 7 years. Mario Dion, the commissioner who found that Trudeau did not break the law, was appointed on the recommendation of Trudeau. Dion resigned, and commissioner Finckenstein was appointed by Trudeau as well.

Conacher explained that the commissioner is then incentivised to make favourable decisions on behalf of the government whenever their seven year term is coming to an end.

“(Dion) ruled on Trudeau. The dangerous thing systemically is if they’re nearing their end of their seven-year term, and they have a case before them that involves the sitting prime minister, they have an incentive to let them off in order to get an appearance of bias. They have this psychological state of mind– presuming they want to be reappointed,” Conacher explained.

Different in every province

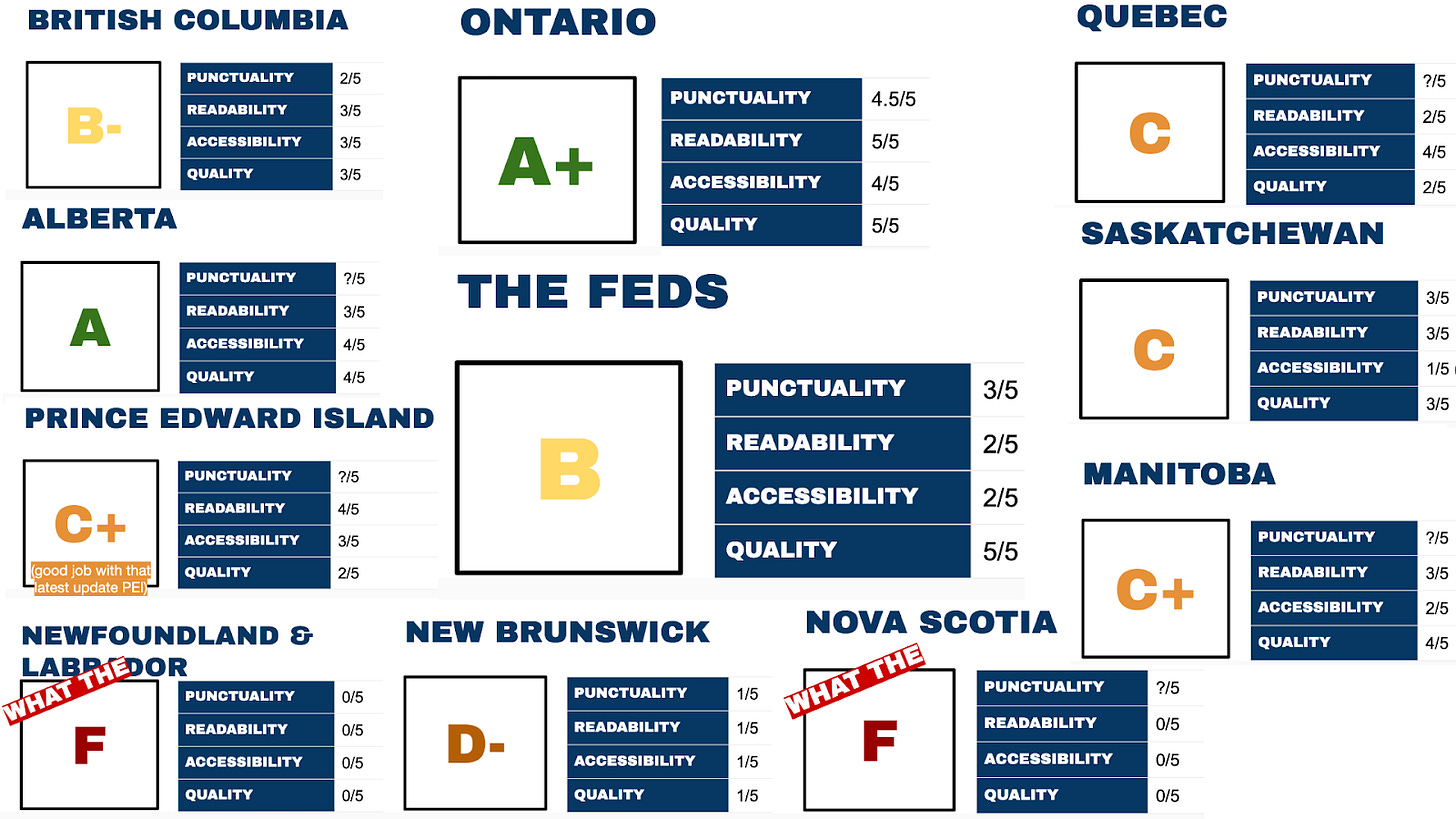

The ethics system is not functioning as it’s supposed to, but it functions well in certain provinces. Aedan crafted a report card to rank how the systems function in each province, based on our research for the disclosures published on his website. This is unscientific and simply for good fun.

Aedan gave the feds a B, but personally I would give them a C, or a C-. Their punctuality is lacking. Their strongest asset is how high quality it is. The information there is much higher quality than the info in most provinces.

Notably, Alberta and Ontario are quite exceptional at providing readable, timely information. This surprised me in compiling our data, but the data available in those provinces is extremely well put together. The enforcement of the laws is clearly sub par, considering the political situations in those two provinces, and the amount of corruption which is openly touted in both Ontario and Alberta, but the information they provide (and that is what this article is about) is quite good.

The worst of the bunch are out east. Nova Scotia and Newfoundland Labrador have terrible disclosures. The Nova Scotian information is handwritten and scanned, often completely unreadable. New Brunswick has similar problems. Meanwhile, NL is even worse– to the point where I was hired to write an entire article about this for the Independent, and the editor and chief, Justin Brake, then did a follow up exposing the level of dysfunction in the commissioner’s office.

To conclude this report– we will see how this court case goes with Democracy Watch and the supreme court. It will be many months before we know, but we will report on it when the decision is finalized. Next week we will return with a report on the MPs who have released their disclosures. We have already finalized all the graphs and numbers, but this piece was simply far too large to do in one report.

This has to be one of the best things I’ve read in years. This is it. In a nutshell. And you even give suggestions on how dissemination/accessibility could be easily remedied. Geez. You’ve literally done more work on this issue than any elected official Ive ever seen. This has been up my arse for decades and it never gets fixed bc the people who are supposed to fix it are the bloody criminals profiting from it. ….yea I’m gonna start swearing so I’ll end here. ❤️ for you and your work. And for Canada’s “ethics” and all those supposedly responsible for it -> 🖕

The closed loop problem you outline here is what makes this so frustrating. Provinces like Ontario and Alberta figuring out timely disclosure while the feds drag their feet for nine months shows this isn't a resources problem, its a priorities problem. Conacher's lapdog comment tracks when you look at how appointments work. Wild that a motivated individual doing free data work is somehow more reliabe than official channels.